Making Academia Better, Part 2 – Create New Interfaces for the Interaction with Industry

Background: In the Netherlands, it is customary to include ‘propositions’ with one’s thesis, essentially opinionated statements defended alongside one’s doctoral work. In this post series, I am outlining the arguments supporting my propositions.

Proposition #6: Universities should establish fellowships that fund stays of industry professionals in academic labs.

Introduction

In a previous post, I argued that the culture of work and research management in industry surpasses that of academia. Industry offers higher salaries and better managerial training, has a larger number of specialized support personnel, generally operates with larger R&D budgets, and implements a range of project management and strategic alignment tools. It also prioritizes reproducibility, automation, and data-driven decision-making to maintain high efficiency and competitiveness.

In this post, I build on this argument and propose a solution: universities should establish fellowships that fund stays of industry researchers and research managers in in academic labs. Such fellowships could significantly improve academic culture, productivity, and relevance. This post will focus on the third aspect – relevance - while touching on improvements to work culture and productivity that have been discussed in my previous post in more detail.

Academia’s core roles

Academia serves two primary purposes, a) training the next generation of researchers, and b) generation of new findings. A third, and b) associated, purpose is c) translation of these findings into practice. Let’s look at these purposes in turn, starting with a) the training.

Training the next generation of researchers

The odds of career as an academic scientist are relatively low. This is an oft discussed feature of the academic career path. 1,2 Only about 20% of PhDs will enter the tenure track, and about 60% of these will be eventually given tenure. 10 years after graduation, about 10% of PhDs will hold scientific staff roles in academic research. The biggest employer of top-school alumni is big tech. This means that around 90% of all academic trainees will not end up working as independent academics. Despite this, their training is predominantly, if not exclusively, geared towards academic skills and performance.

Data on the extent to which the current nature of academic training negatively impacts workforce productivity is lacking. However, anecdotal evidence is plentiful. Those familiar with academia often know individuals who have struggled to find jobs aligned with their training, whether immediately after earning their PhD or following a period as a postdoc. This frequently results in unplanned unemployment or acceptance of roles for which they are overqualified, undermining the time and financial investment in their education. Such outcomes represent economic losses and highlight a failure to build relevant career capital. Change is essential, and new approaches are needed to enhance the relevance of academic training.

I can offer some examples on how we could achieve this, drawn from my time as a PhD candidate. During this period, I engaged with smart people through organizations like iGEM, Nucleate, Global Biotech Revolution and BlueDot Impact. One type of experience that influenced me was working with young, ambitious, intelligent and kind people. I got to write papers with smart undergrads, learn alongside highly productive teammates, and collaborate with visionary prospective entrepreneurs. These experiences influenced my academic thinking and strategic planning abilities as much as my experience as an academic trainee.

Another valuable learning experience was founding Nucleate Netherlands. This role exposed me to a culture with an accent on quality of presentation (e.g. branding), and the nature of ‘always being ready’, as well as fostered supportiveness for personal agency and proactive effort. It also allowed me to delve into the Dutch and European startup scene and understand some of its challenges and opportunities. Additionally, it was another great chance to work alongside bright people, learning from their approaches to managing projects and priorities.

Generation of new findings

Let’s examine the second key task of academic institutions, generating new findings, and its corollary, translating them into practice.

Academic institutions generally excel at creating new knowledge. This aspect is heavily measured and ranked, making it a primary focus for universities and research institutions. However, in my view, not enough attention is given to triage on relevance and significance of these findings. While current approach helps the production of academic papers, their impact outside academia varies widely.

This variability is inherent to research - some findings and researchers will have an outsized impact. Nonetheless, some aspects of the current system can be improved. We must critically evaluate the research we pursue, prioritizing projects with either breakthrough potential or good pathways to translation. The “middle ground” tends to offer the lowest return on investment (See my other post on curiosity- vs need-driven research).

Proposed solution – Fellowships for industry professionals

Above, I highlighted two important issues in academia – the inappropriateness of academic training for majority of post-academic careers, and the highly variable level of relevance of academic research. I believe that fellowships funding stays of industry professionals in academic labs and institutions could help address both.

Increasing relevance of academic training

First, inviting industry professionals to spend time in academic labs as scientists and managers establishes a new interface for knowledge transfer. Academic trainees will get the opportunity to consider problems from new perspectives, explore different solutions, and contextualize their research in industry-relevant contexts. Additionally, they will get exposed to more sophisticated managerial culture, develop appreciation for strategic planning, and build valuable professional connections.

As I have illustrated through my personal experiences of working with students above, this arrangement can be mutually beneficial. The industry fellows are likely to benefit from meeting young trainees, for example by getting easier access to new research findings, developing better appreciation for younger colleagues, and finding increased job satisfaction through mentorship.

Increasing relevance of academic research

In addition to enhancing training, inviting industry professionals to academic labs can also help increase the relevance of academic output by helping to identify research that has high potential to be translatable as well as to weed out the one that does not. It can help to suggest new areas for research that correspond to currently pressing industry needs.

In turn, academics will be freer to dedicate time to focus on developing research paths with breakthrough potential, the most important and impactful domain of academic research. Finally, academic grants frequently require some industry collaboration or co-investment, or at least ideas for commercialization. Connections to industry and opportunities for early vetting of such ideas would be of high value to any academic and facilitated through the type of fellowship proposed here.

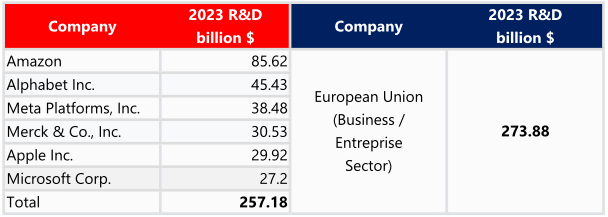

Beyond the benefits to academia, spending time in academic labs is likely to have unique benefits for industry scientists as well. Industry R&D is generally more focused, and, in many cases, unable to dedicate resources for pursuing projects that are longer or riskier than some threshold. This has been subject to much scrutiny, with critiques claiming that ‘the industry ceased to innovate’ (an example from pharma). This is overblown. Industry is, by far, the largest R&D spender. I find this quite impressive - the five largest tech companies (Amazon, Google, Meta, Apple and Microsoft), plus one big pharma (Merck) spent nearly as much as the whole industry within European Union. This itself is more than six-fold more than all the EU governments have spent combined. 3,4 It is, however, true that in the past few decades, industry generally shifted to a model where access to a significant portion of innovation comes through the acquisition of outside firms (although this may be changing 5). Startups are closer to the newest technology, tend to be more time and resource efficient, and are generally the right place for people with a larger appetite for risk.

The collaboration between startups and industry is generally effective, but there is room for improvement through enhanced opportunities for exchange. Consider this, fairly common, example, industry professionals may have advanced understanding of internal bottlenecks and problem spaces, yet no startups are actively developing appropriate solutions to address them. Prioritizing the communication of these needs to the right audiences is an important benefit to industry.

From my work with Nucleate, a global community for entrepreneurial academic trainees, I’ve observed that students, graduate students, and postdocs are incredibly valuable to industry stakeholders. Many large companies have budgets allocated for startups tackling critical problems and opportunities the industry has identified. These companies are eager to engage students early, supporting them in transforming academic projects into startups and applications more broadly. This creates a win-win dynamic: academics work on relevant problems with commercialization paths, while industry gains access to innovative startups early - often at a relatively low cost.

The utility of fellowships for industry professionals also holds when we consider the industry as the primary benefactor. It is not uncommon for industry scientists to have solution or product ideas themselves, but they may be unable to pursue them internally due to their technology risk profile, tangency to core business, or long development timelines.

Providing industry scientists with opportunities to spend time in academic labs through fellowships could create unique windows for exploring such ideas. One example from my personal experience illustrates this well. As a master’s student, I worked in a lab where several researchers were developing focal molography. 6 The initial concept for this technology came from a scientist at Roche.

This individual took the initiative to establish a collaborative relationship with an academic group, where he was eventually able to incubate the idea through collaboration with PhDs and postdocs. His proactive approach paid off: the technology became a resounding success. In addition to multiple publications, it led to the creation of a startup founded by the academic trainees who developed the technology. That startup was later acquired by a major biopharma supplier company and is now delivering its first commercial instrument to customers.

I find this example particularly inspiring, as it represents another multi-party win-win scenario. The inventor was able to translate his vision to reality, while the PhDs and postdocs worked on challenging and meaningful problems, all of them ultimately benefiting from the startup’s establishment and acquisition. Roche, the inventor’s employer, also benefited by gaining a novel instrument for its early R&D pipeline, which specifications and features it even could help shape during development. The professor who hosted the collaboration saw success as well, with his group publishing good papers, filing patents, and receiving industry funding. Finally, the university also benefited by adding a startup they can brag about to its portfolio.

Conclusion - Path to implementation

I hope that the above arguments and examples have made you more inclined to consider the opportunities such fellowship represents for both academic and industry scientists. An important question is, how would we go about implementing this? First, governments should collaborate with universities to allocate funding. Second, implementing organizations would have to work closely with industry to ensure the way the program is implemented does not subtract from the idea’s attractiveness for scientists on both sides. Handling intellectual property, for example, could become a sensitive issue. Similarly, the different cultures of work and the strong emphasis on academic independence may create friction during the program’s early stages.

These challenges can only be addressed through experience. Aside from isolated examples, like the Roche scientist I mentioned earlier, or an occasional sabbatical taken by a top industry scientist at an academic lab, there are few established models or best practices for such fellowships. That said, promising developments are emerging. This fall, ARIA (the Advanced Research and Innovation Agency), in collaboration with Pillar VC, has announced a program to fund academic fellowships for leading AI industry scientists. ARIA is the UK’s vehicle for reviving the British innovation engine, so it is really exciting to see them take up this initiative. While the program’s first fellows will only begin in 2025, the initiative merits close attention from other countries. If successful, it could serve as a blueprint for similar initiative elsewhere.

References

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-024-02351-8#Sec1 ↩

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-34809-1.pdf ↩

-

https://www.rdworldonline.com/top-30-rd-spending-leaders-2023-big-tech-firms-hit-new-heights/ ↩

-

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=R%26D_expenditure ↩

-

Google published 20 times more papers in 2019 than in 2005. Amazon has grown their publication rate by more than 10 times in just 5 years, as per Maxwell Tabarrok. ↩

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/nnano.2017.168 ↩

comments powered by Disqus