Get the (S)hell Back Here!

Background: In the Netherlands, it is customary to include ‘propositions’, essentially opinionated statements defended alongside one’s doctoral work. In this post series, I am outlining the arguments supporting my propositions.

Proposition #10: The benefits of Shell’s residency in the Netherlands far outweighed its environmental controversies.

Introduction

Shell, one of the world’s largest and most recognizable energy companies, has long been a titan in the global market. Founded in 1907 through the merger of Royal Dutch Petroleum and the Shell Transport and Trading Company, it boasts a market capitalization of about $200 billion and operations spanning nearly 100 countries. Shell is synonymous with innovation and resilience in the energy sector - but also with controversy.

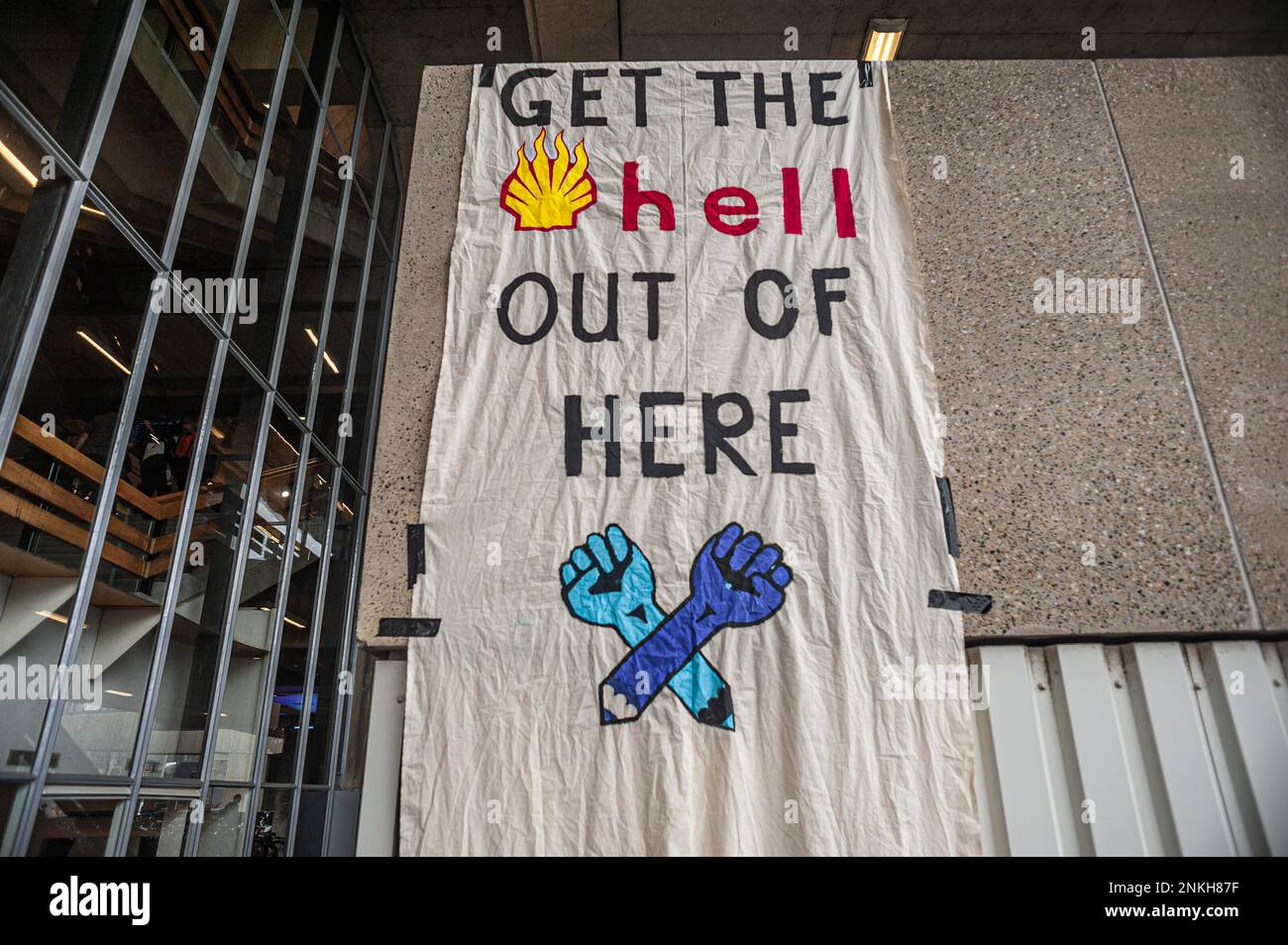

In the Netherlands, the birthplace of its Royal Dutch heritage, Shell’s reputation is complicated. Critics highlight its environmental record, legal battles over oil spills in Nigeria, and accusations of insufficient action on climate change. The company’s prominent role in Dutch society has often made it a lightning rod for environmental and social protests.

Originally formed in a Dutch-British structure, in 2021, the company made a historic decision: to move its headquarters entirely to the United Kingdom. The move, presented as company’s larger strategy in a changing energy landscape, appeared motivated by the aim to escpae increasingly unfriendly Dutch business environment and environmental lawsuits. In this article, I want to argue that this move has negatively impacted the Dutch innovation and economic landscape, and that the Dutch made a mistake in putting their environmental wokeness above their economic interests.

Shell’s history

Shell’s predecessors

The Royal Dutch Petroleum Company was founded in 1890 by August Kessler and Henri Deterding in the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia). The company was established to develop and export oil discovered in these regions, with its operations crucial for turning oil into a strategic resource for industrial economies. By the late 19th century, Royal Dutch had become a significant player in the oil industry.

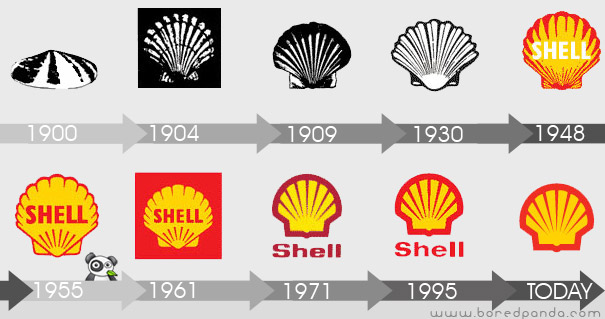

Meanwhile, the Shell Transport and Trading Company emerged in 1833 as a small London-based firm trading seashells, founded by Marcus Samuel. By the 1890s, under the leadership of Marcus Samuel Jr., the company shifted to transporting kerosene from the Caspian Sea region. Samuel’s innovative use of oil tankers capable of traversing the Suez Canal positioned Shell as a key player in the global oil trade.

Company merger and creation of modern Shell

In 1907, the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company and the Shell Transport and Trading Company merged to create the Royal Dutch Shell Group. The merger was driven by intense competition with Standard Oil and the growing demand for efficient global oil distribution. Henri Deterding, often called “The Napoleon of Oil,” played a pivotal role in this unification, recognizing the benefits of combining Royal Dutch’s production strength with Shell’s transportation and marketing expertise.

The dual Dutch-British structure emerged from the companies’ respective national identities. Royal Dutch owned 60% of the merged entity, and Shell Transport held 40%. This arrangement allowed the company to leverage financial and strategic advantages in both nations, such as tax benefits, access to capital markets, and diversified operational bases.

Shell’s innovation

Shell’s history is marked by numerous technical achievements. The company was a pioneer in the development of seismic surveying techniques for oil exploration starting from 1920s. These methods allowed for more accurate mapping of geological formations, which improved oil discovery rates both on land and underwater. Shell also developed advanced refining processes for transforming crude oil into high-value products. This included hydrocracking, which refers to breaking of carbon-carbon bonds in complex hydrocarbons with the aid of hydrogen, yielding shorter chains. This technique is used for example to produce diesel and kerosene. Shell is one of the licensors of the technology and continues to advance it, e.g. through introduction of new catalysts.1,2

As oil exploration continued, newly discovered surface reserves were becoming less profitable. Companies gradually shifted to offshore exploration. While basically negligible in the early 50’s, offshore now accounts for about 30% of global oil production. According to current estimates, half of all remaining reserves are offshore, quarter of that being in deepwater. Shell has made significant advancements in deepwater drilling technologies in past decades, enabling access to previously untapped oil reserves. This is exemplified with Shell’s ‘Mars’, one of the largest deepwater rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. The prospecting work started in 1985, and the first platform entered production in 1996, netting establishment costs of more than $1B. Second platform, Mars B Olympus, opened in 2014, extending the field’s lifetime to at least to 2050.3

Shell has also been a pioneer in the development of gas-to-liquids (GTL) conversion, particularly through the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis process, with number of patents in the area.4 The technique enables natural gas to be transformed into liquid fuels and other products. Nowadays, Shell’s GTL facility in Qatar, known as Pearl GTL, is the largest and most advanced GTL plant globally. The plant represents over 50% of the world’s total commercial-scale GTL capacity. Together with smaller plants, this means that Shell controls nearly 75% of all the GTL capacity worldwide.

The production capacity and process knowledge help to cement Shell’s position in the field of lubricants, where it is a market leader for 17 consecutive years. Similarly, Shell is one of the leaders in production of low-carbon synthetic fuels, that particularly attractive as ways to reduce emissions in hard-to-decarbonize sectors such as aviation and shipping.5 More recently, Shell has been investing in renewables and new energy technologies, including building wind farms, acquiring solar capacity, developing carbon capture and storage and green hydrogen production.6

Shell’s early recognition for the potential of oil and gas business, and the drive for innovation baked into its DNA, quickly positioned it to become one of the leaders in oil production and distribution worldwide. By the mid-20th century, Shell was producing approximately 11% of the world’s crude oil supply and owning about 10% of global tanker tonnage. Nowadays, Shell continues to belong to top 10 crude oil producers worldwide, but its market share has fallen to about 3%. Correspondingly, Shell now owns 2% of the global tanker tonnage.

Shell’s controversies

Shell being a major player in discovery and utilization of one of the most valuable natural resources, its global operations often intersected with geopolitical tensions and caused environmental concerns.

One of its earliest controversies involved its role in the Nigerian oil industry. By the 1950s, Shell’s operations in the Niger Delta began raising alarms due to environmental degradation and displacement of local communities. Shell even faced lawsuits alleging complicity in human rights abuses in Nigeria.7 The most notable case involved accusation of the company’s role in executions of local activists.

Throughout its history, Shell has been one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, ranking 9th in the period from 1988 to 2015.8 The controversy that likely shaped today’s view of the company the most dates back to late 80’s and early 90’s. It likely started with very good intentions. In 1991, Shell produced a 28-minute documentary about the effects of fossil fuel economy on the climate. The movie was made for public, schools and universities. It raised a clear and sound alarm about industry’s role in global warming, and its potential consequences, including floods, famine, and populational displacement. The science on climate change was only being established, but the film’s message was endorsed by broad scientific consensus.

Then, Shell slipped. Shortly after the film went public, the company distanced itself from it and stopped distributing it. It was only in 2017, when the Dutch newspaper De Correspondent got access to the movie, that its existence became widely known and discussed. This further deteriorated Shell’s public image, the company already being under heavy security due to its lobbying against renewable energy targets, and against science backing climate change, in the years prior. To make matters even worse, it turned out that Shell had confidential internal documents pointing to man-induced climate change dating as far back as 1986.

In 2019, group of Dutch environmental scientists and NGOs, together with more than 17’000 citizens sued Shell. They accused the company from ongoing harm to climate despite being in possession of evidence of global warming, suing them for hazardous negligence. In 2021, the Dutch court ruled that Shell must reduce its CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030. Shell contested, arguing that it is already doing enough, and if more needs to be done, the guidelines should be implemented by governments, not private companies. The court’s 2021 decision has been repealed in November 2024. In 2022, Shell was, along with BP, Chevron Corporation, and ExxonMobil, accused from greenwashing by the U.S. House Oversight and Reform Committee.

Shell has taken action to reduce its carbon footprint in recent years, but the public sees this as lackluster and insufficient. The company continues to engage in environmentally concerning practices. For example, through 2022, Shell pursued seismic oil reserve exploration off the South African coast. This effort, criticized by environmentalists, can potentially interfere with migratory and breeding patterns of whales in these areas and permanently alter the coastal marine ecosystems.9

Get the (S)hell back here!

Contextualizing Shell’s environmental impact

Shell’s history as a global energy player is as much a story of innovation as it is of environmental controversy. While its operations have undoubtedly contributed to greenhouse gas emissions, they are tied to the fundamental realities of the oil and gas sector.

While it is clear that the oil and gas industry must innovate, the responsibility for reducing emissions has to extend beyond these companies. Transformation is needed across industries. Governments, not publicly traded companies, must take the lead in driving these systemic changes. Public companies like Shell operate under the imperative of maximizing shareholder returns, which inherently limits their ability to prioritize long-term environmental goals over short-term profitability. Ignoring this this means ignoring how market works.

Operations like crude oil extraction and transportation are carried out by many industry players and are inevitably interfering with the environment. Chemical processes, in particular the Fischer-Tropsch GTL conversion, are extremely energy intensive, yet essential for producing fuels and materials much of our society depends on. These processes currently have no viable scalable substitutes. The rising global demand for energy - fueled by population growth and the expanding middle class – unavoidably necessitates continued reliance on carbon-based energy sources in the near term.

Finally, Shell’s efforts to address environmental concerns should not be overlooked. In 2024, the company pledged to invest $10 to $15 billion in renewable energy projects by 2026. In terms of share of total investment this is comparable to other oil and gas industry leaders.

Benefits of Shells’ domicile in the Netherlands

Tax Revenue and R&D Spending

Shell’s presence in the Netherlands brought substantial tax revenues that supported public programs and infrastructure. In 2021, when Shell maintained its dual-residency structure, Shell’s tax contributions to Dutch authorities exceeded $165M. In the same year, the tax contributions to the UK were only $54M.10 Conversely, in 2023 after movement of the company entirely to the UK, the corporate tax payable to the Netherlands reached $314M, while that payable to UK jumped to $1’450M.11

Historically, Shell belonged to some of the major R&D investors in the Netherlands. In 1999, with €171M, it was the 3rd biggest spender in this area.12 Recent economic research indicates that Shell’s energy-related investments in the Netherlands have exceeded €3B between 2016 and 2021, and its Dutch R&D expenditure reached €60M annually between 2011 and 2022.13 While data on R&D spending in the Netherlands after 2022 is not available, governmental reports expect that the company will behave as similar companies worldwide, shifting parts of its R&D spending to new country of its residence, the UK.14

Talent Development and Strategic Expertise

Shell’s operations also provided Dutch professionals with unique opportunities for career growth. The company’s managerial positions exposed employees to global-scale challenges, in an industry with an outsized impact, offering hard-to-replace training opportunities and experience. This pipeline of skilled talent not only benefited Shell but also enriched the broader Dutch economy as individuals moved on to work in other positions across the industry, or mentor and teach others.15

Despite progress in renewable energy, oil and gas will remain critical to global energy supply for decades, making Shell’s technical and business expertise highly relevant. But besides oil and gas, Shell’s expertise is relevant in other, equally critical areas. One example is the discovery and mining of critical materials and metals. These elements represent strategic resources for energy storage and conversion, as well as semiconductor manufacturing. Indeed, they have been a cause for recent geopolitical tensions. Another area where Shell’s expertise has immense value is geothermal energy, the thermal energy extracted from Earth’s crust. It is estimated that the amount of energy stored there is more than 40-fold that of all known petroleum and nuclear fuel reserves. Geothermal, therefore, offers a sustainable energy alternative, without the on-and-off inconveniences of renewables like wind, and solar. Finally, more futuristic undertakings such as asteroid mining and lunar water extraction could both benefit from the unique expertise of oil and gas companies like Shell.

Conclusion

Shell’s history is one of duality: a pioneer of innovation and a source of controversy. While Shell’s environmental controversies are serious, they are not entirely unique to the company. As a part of a broader systemic challenge, they require collective action. The role of publicly traded companies in addressing these challenges can be only a limited one.

Instead of driving Shell away, the Netherlands should have worked on strategically aligning goals, and leveraging its presence to further both economic and environmental goals, fostering innovation and collaboration in addressing global energy challenges. By prioritizing wokeness over a pragmatic understanding of business and market dynamics, the Netherlands lost a valuable corporate partner that it may never be able to recreate.

Further reading

Patents

- Patents relating to the Fischer-Tropsch process

- https://patents.google.com/?assignee=Shell+Internationale+Research+Maatschappij+B.V.

- https://patents.google.com/?assignee=SHELL+OIL+COMPANY

- https://patents.justia.com/assignee/shell-oil-company

Seismic technology

- History of Seismic In The Gulf of Mexico

- Exploration Seismology (textbook)

- The History and Development of Seismic Prospecting

- Seismic Method

- Seismic Technology - Offshore Exploration and Production

Gas-to-liquids conversion

Deepwater prospecting and oil recovery

Hydrocracking

- A Brief History of Oil Refining

- Shell Catalysts & Technologies - Next-Level Hydrocracker Flexibility

Geothermal

More on Shell

References

-

https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6092581 ↩

-

https://catalysts.shell.com/hubfs/SCT_ParadigmBusters.pdf?hsLang=en ↩

-

https://www.offshore-technology.com/projects/mars-b-olympus-project-gulf-of-mexico/?cf-view ↩

-

https://www.fischer-tropsch.org/primary_documents/patents/pattoc.htm ↩

-

https://www.kenresearch.com/industry-reports/global-synthetic-fuel-market ↩

-

https://blog.wearedrew.co/en/shell-case-study-innovating-for-a-clean-energy-future ↩

-

https://www.cetim.ch/cases-of-environmental-human-rights-violations-by-shell-in-nigeria%E2%80%99s-niger-delta/ ↩

-

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2017/jul/10/100-fossil-fuel-companies-investors-responsible-71-global-emissions-cdp-study-climate-change ↩

-

https://undark.org/2022/02/10/whale-ears-shell-oil-and-the-hidden-toll-of-seismic-surveys/ ↩

-

https://www.shell.com/news-and-insights/annual-reports-and-publications/tax-contribution-report ↩

-

https://www.shell.com/news-and-insights/annual-reports-and-publications/tax-contribution-report ↩

-

https://vector.tno.nl/en/articles/top-30-companies-investing-most/ ↩

-

https://www.shell.nl/about-us/news/2022/investeerders-in-de-nederlandse-energietransitie ↩

-

https://www.bedrijvenbeleidinbeeld.nl/bouwstenen-bedrijvenbeleid/documenten/publicaties/2024/10/15/index ↩

-

I have an interesting example of this. Recently, a new Dutch contract research organization developing formulations of RNA therapeutics was established. The company is led by a former Shell executive. This individual retired early, then got bored, and joined the National Growth Program, where he came across scientific work that attracted his interest. He recognized a business opportunity, contacted the scientists, and together they launched a new company. ↩

comments powered by Disqus